CONGRATULATIONS TO OUR CLASS OF 2024 INDUCTEES!

Making a Mark in Blues History

The Blues Foundation’s Blues Hall of Fame honors those who have made the Blues timeless through performance, documentation, and recording. Since its inception in 1980, The Blues Foundation has inducted new members annually into the Blues Hall of Fame for their historical contribution, impact, and overall influence on the Blues. Members are inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame in five categories: Performers, Individuals, Classic of Blues Literature, Classic of Blues Recording (Song), and Classic of Blues Recording (Album). Since 1980, The Blues Foundation has inducted over 400 industry professionals, recordings, and literature into the Blues Hall of Fame. Of the 130 performer inductees, 120 of them are African-American.

An anonymous committee of Blues scholars and experts representing all subsets of Blues music convenes each year to review potential Blues Hall of Fame candidates. Recommendations are shared with the committee via The Blues Foundation offices, but we do not accept active campaigns for any potential inductee in order to keep this process fair, devoid of political overtones, and based upon actual contributions rather than individual popularity. Candidates selected for induction are determined exclusively on their body of work over their lifetime. Names of all inductees are released to the public each spring. The Blues Foundation hosts a special Blues Hall of Fame Induction ceremony, held annually on the evening before The Blues Music Awards, as a ticketed event open to the public.

Blues Hall of Fame Museum

Opened on May 8, 2015, the Blues Hall of Fame Museum serves the community as a center for people to enjoy physical exhibits honoring the legends of Blues. Located in downtown Memphis – across the street from the National Civil Rights Museum – the museum holds the history and music of Blues greats for visitors to enjoy year-round.

The Blues Foundation’s 2024 Blues Hall of Fame Inductees

Blues Hall of Fame Inductee biographies and descriptions were researched and written by Jim O’Neal (bluesoterica.com) with thanks to Bob Eagle, Bob McGrath, John Broven, Roger Armstrong, Larry Cohn, Malaco Records, and Roger Naber.

Performers

Sugar Pie DeSanto packed astonishing power and plenty of personality into a tiny frame. Her spunk and vigor impressed bandleader and producer Johnny Otis enough to sign her to her first recording session in 1955 after witnessing her performance at a San Francisco talent show. It was Otis who named her Sugar Pie in preference to using her given name, Peylia Balinton. A ballet student as a child, she was born in Brooklyn on October 16, 1935, to a Filipino father and African American mother, but grew up in the Bay Area and continued to live there except for a spell in Chicago when she was with Chess Records in the 1960s. After her 1955 debut for Federal Records, Sugar Pie recorded a few more singles, often with her husband, guitarist Alvin Parham, aka Pee Wee Kingsley, acquiring the DeSanto moniker from producer/DJ/club owner Don Barksdale.

Sugar Pie DeSanto packed astonishing power and plenty of personality into a tiny frame. Her spunk and vigor impressed bandleader and producer Johnny Otis enough to sign her to her first recording session in 1955 after witnessing her performance at a San Francisco talent show. It was Otis who named her Sugar Pie in preference to using her given name, Peylia Balinton. A ballet student as a child, she was born in Brooklyn on October 16, 1935, to a Filipino father and African American mother, but grew up in the Bay Area and continued to live there except for a spell in Chicago when she was with Chess Records in the 1960s. After her 1955 debut for Federal Records, Sugar Pie recorded a few more singles, often with her husband, guitarist Alvin Parham, aka Pee Wee Kingsley, acquiring the DeSanto moniker from producer/DJ/club owner Don Barksdale.

Her biggest hit, “I Want to Know,” produced by Bob Geddins on the Veltone label, rose to No. 4 on Billboard’s R&B chart in 1960 and led to a contract with Chess. The DeSanto magic also energized the already dynamic James Brown revue for two years. During her tenure with Chess, she had some hits on the subsidiary Checker label, including “Slip-In Mules,” an answer to Tommy Tucker’s “Hi-Heel Sneakers, and “In the Basement” on the Cadet imprint, a duet with longtime friend Etta James, who was often at the Balinton home as a youngster. Sugar Pie’s records also clicked with the Northern Soul crowd in England, enough so that she left the all-star cast of the 1964 American Folk Blues Festival’s European tour to make U.K. appearances of her own. Under various names including Peylia Parham and P. Parham DeSanto she began writing songs for other artists at Chess, including Billy Stewart, Fontella Bass, and Little Milton. Sugar Pie took her act back to Oakland and remained active and still saucy even into her octogenarian years, a local favorite as well as a world traveler.

When times were slow, she worked as a paralegal. The Rhythm & Blues Foundation provided support after she lost her husband Jessie Davis in a fire at their apartment. The Foundation also presented her with a Pioneer Award, one of several honors she has earned from various sponsors, including the Arhoolie Foundation and Blues Blast magazine. She found a recording home with her manager James C. Moore’s Jasman label, which began releasing DeSanto’s output in 1972, sprinkling her catalog with titles befitting her persona such as Sugar Is Salty, Refined Sugar, and Sugar’s Suite.

Lurrie Bell, a prominent figure in the blues world, follows in the footsteps of his late father, harmonica maestro Carey Bell, who was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame in 2023. Born on December 13, 1958, in Chicago, Lurrie developed into an extraordinary blues guitarist during the 1970s, displaying remarkable talent even as a teenager. Despite facing personal trauma and tragedy throughout his life, Lurrie’s enduring passion for music has carried him into his senior years with the same youthful exuberance. Growing up in a musical environment, Lurrie drew inspiration from his father’s musical circle, notably guitarist Eddie Taylor.

Lurrie Bell, a prominent figure in the blues world, follows in the footsteps of his late father, harmonica maestro Carey Bell, who was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame in 2023. Born on December 13, 1958, in Chicago, Lurrie developed into an extraordinary blues guitarist during the 1970s, displaying remarkable talent even as a teenager. Despite facing personal trauma and tragedy throughout his life, Lurrie’s enduring passion for music has carried him into his senior years with the same youthful exuberance. Growing up in a musical environment, Lurrie drew inspiration from his father’s musical circle, notably guitarist Eddie Taylor.

His early experiences included playing in a band with pianist Lovie Lee, the musician credited with bringing Carey Bell to Chicago from Mississippi. Lurrie’s childhood also involved living in Mississippi and Alabama, where he played gospel music in church alongside his Bell brothers, collectively known as “The Ding Dongs.” Lurrie’s journey into professional music began in 1977 when he recorded on a session with his father, Carey Bell, and played bass on an Eddie C. Campbell album. That same year, he joined forces with Billy Branch and other emerging blues musicians in the “New Generation of Chicago Blues” package in Berlin. The collaboration with Branch evolved into the Sons of the Blues (S.O.B.) band, solidifying Lurrie’s status as one of the rising stars in the blues scene. His guitar skills and innate understanding of the blues genre gained recognition as he recorded with various artists, including Koko Taylor, Eddy Clearwater, Sunnyland Slim, and Louisiana Red. Despite personal challenges, including periods of depression, isolation, and life on the streets, Lurrie’s musical talents continued to captivate audiences.

His life took a challenging turn with the passing of his partner, photographer Susan Greenberg, and the heartbreaking loss of their twin babies. Carey Bell’s death in 2007 added to the hardships, yet Lurrie’s unique musical abilities served as a lifeline, bringing him back to a sense of sanity. Over the years, Lurrie faced personal challenges, but his musical journey persisted. Amberly Stokes, a devoted supporter and former Rosa’s Lounge employee, became Lurrie Bell’s advocate. Under her care and management, he found stability, a supportive home life, and renewed worldwide acclaim for his remarkable talent. Lurrie’s enduring contribution to the blues genre, resilience, and captivating performances solidified his place in the Blues Hall of Fame.

Odetta, hailed as “The Mother Goddess of Folk Blues” by The New York Times, left an indelible mark on the world of folk music for five decades. Her influential career not only showcased her extraordinary musical talents but also paved the way for others, breaking barriers as a woman and an African American in the folk milieu. Born Odetta Holmes on December 31, 1930, in Birmingham, Alabama, she spent most of her childhood in Los Angeles. Classically trained in college, Odetta possessed a versatile repertoire that spanned blues, spirituals, jazz, songs from various folk and popular traditions, and original topical songs reflecting her commitment as a civil rights activist.

Odetta, hailed as “The Mother Goddess of Folk Blues” by The New York Times, left an indelible mark on the world of folk music for five decades. Her influential career not only showcased her extraordinary musical talents but also paved the way for others, breaking barriers as a woman and an African American in the folk milieu. Born Odetta Holmes on December 31, 1930, in Birmingham, Alabama, she spent most of her childhood in Los Angeles. Classically trained in college, Odetta possessed a versatile repertoire that spanned blues, spirituals, jazz, songs from various folk and popular traditions, and original topical songs reflecting her commitment as a civil rights activist.

Although she occasionally worked the blues club and festival circuit, her blues credentials were undeniable, evident in albums like “Odetta Sings Blues and Ballad,” “Odetta and the Blues,” “Blues Everywhere I Go,” and “Lookin for a Home,” a compilation featuring songs associated with Lead Belly. Her remarkable career included performances in Martin Scorsese’s 2003 “Salute to the Blues” concert, Divas film in Clarksdale, Mississippi, and appearances at the Apollo Theater in Harlem and Blues Foundation events. Odetta, who was once married to blues singer Louisiana Red, enchanted audiences with her magnetic stage presence and powerful voice, captivating listeners whether singing solo or collaborating with symphony orchestras, jazz bands, ballet troupes, opera companies, or all-star musical aggregations. Odetta’s commitment to social justice was evident as she sang at historic events like the March on Washington and the Selma, Alabama March, as well as at human rights and anti-war rallies. She used her voice not only to entertain but also to advocate for change, performing at benefits, tribute concerts, and schools.

Throughout her illustrious career, Odetta collaborated with luminaries such as Harry Belafonte, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Nina Simone, Maya Angelou, and Pete Seeger. Her influence extended to artists like Bob Dylan, Janis Joplin, Joan Baez, Rhiannon Giddens, Eric Bibb, and countless others. Honored by U.S. presidents, the Library of Congress, and numerous organizations worldwide, Odetta continued to perform even in the face of declining health. She passed away in New York on December 2, 2008, leaving behind a legacy that transcends music, resonating in the realms of humanitarianism and education.

Jimmy Rushing, affectionately known as “Mr. Five By Five” due to his stout stature, was a groundbreaking figure in the world of blues and jazz. Born on June 15 or August 26, 1899 (though he often cited a 1901 birth-date), in Oklahoma City, James Andrew Rushing pioneered the big band blues belting style, leaving an indelible mark on the genre and influencing subsequent blues shouters like Big Joe Turner, Wynonie Harris, and Roy Brown. Inspired by an uncle, Rushing began his blues journey in California in 1923, where he played piano with Jelly Roll Morton before returning to Oklahoma.

Jimmy Rushing, affectionately known as “Mr. Five By Five” due to his stout stature, was a groundbreaking figure in the world of blues and jazz. Born on June 15 or August 26, 1899 (though he often cited a 1901 birth-date), in Oklahoma City, James Andrew Rushing pioneered the big band blues belting style, leaving an indelible mark on the genre and influencing subsequent blues shouters like Big Joe Turner, Wynonie Harris, and Roy Brown. Inspired by an uncle, Rushing began his blues journey in California in 1923, where he played piano with Jelly Roll Morton before returning to Oklahoma.

He sang in various territory bands, including Walter Page’s Blue Devils, and joined Bennie Moten’s Kansas City Orchestra, marking the beginning of his association with legendary jazz figures. Rushing recorded or performed with luminaries such as Count Basie, Buck Clayton, Benny Goodman, Dizzy Gillespie, Earl “Fatha” Hines, and others. He was the vocalist on the Johnny Otis orchestra’s inaugural record in 1945 and reunited with Otis at the 1970 Monterey Jazz Festival. Rushing’s pivotal recordings with the popular Basie band, starting in 1935, catapulted him to national prominence. Hits like “Good Morning Blues,” “Going to Chicago,” and “Sent for You Yesterday and Here You Come Today” showcased his commanding vocal presence and marked him as a leading figure in the big band era. He played a significant role in bringing blues to a broader audience. After moving to New York City in the 1950s, Rushing continued his prolific recording and touring career.

He worked with various labels, including Vanguard, Columbia, ABC BluesWay, and RCA, releasing albums like “Livin’ the Blues” and “The You and Me That Used to Be.” Despite battling leukemia in his final years, Rushing continued to receive accolades, posthumously winning a Down Beat magazine poll as Best Male Singer shortly after his death in June 1972. Rushing’s contributions to blues and jazz were immeasurable, bridging the gap between the genres and influencing a wide array of singers. Although recognition may have faded among more recent generations of blues enthusiasts, his impact on blues, jazz, pop, and rhythm & blues remains undeniable. Rushing’s career reached far and wide, spreading the appeal of the blues to a broader audience than ever imagined.

Scrapper Blackwell, born Francis Hillman Blackwell, left an indelible mark on the blues scene as a virtuoso guitarist and collaborator with Blues Hall of Famer Leroy Carr. Though widely recognized for his role in the iconic Carr-Blackwell duo during their recording zenith from 1928 to 1935, Blackwell’s musical prowess extended far beyond accompaniment. Born on February 21, 1903 (though birth details remain uncertain, with some evidence pointing to Indianapolis in 1904), Blackwell, of Cherokee and African-American descent, began his artistic journey crafting makeshift guitars as a child.

Scrapper Blackwell, born Francis Hillman Blackwell, left an indelible mark on the blues scene as a virtuoso guitarist and collaborator with Blues Hall of Famer Leroy Carr. Though widely recognized for his role in the iconic Carr-Blackwell duo during their recording zenith from 1928 to 1935, Blackwell’s musical prowess extended far beyond accompaniment. Born on February 21, 1903 (though birth details remain uncertain, with some evidence pointing to Indianapolis in 1904), Blackwell, of Cherokee and African-American descent, began his artistic journey crafting makeshift guitars as a child.

His entry into the blues arena was catalyzed when he joined forces with Leroy Carr in 1928. The duo’s sessions yielded timeless classics, with hits like “How Long—How Long Blues” making them a household name. Despite their success, Carr’s untimely death in 1935 led Blackwell to retreat from music, only to be rediscovered by local fans in the 1950s. His raw talent and unique guitar style were showcased in solo recordings and collaborations with emerging musicians. Yazoo Records acknowledged his unparalleled guitar skills, emphasizing his ability to blend heavy bass sections and intricate treble-string runs. In the 1950s, Indianapolis jazz scholar Duncan Schiedt reintroduced Blackwell to a new generation of fans who admired his old recordings. Despite facing periods of unemployment, Blackwell continued to play in local taverns and mentor aspiring musicians.

His unexpected encounters with old admirers led to concert performances and recordings, contributing to the folk-blues revival of the late 1950s and early 1960s. Nicknamed “Scrapper” for his youthful inclination for tussles, Blackwell’s life was marked by both musical triumphs and personal challenges. His journey came to an unfortunate end on October 7, 1962, when he was discovered in an Indianapolis alley, having succumbed to two .22 caliber bullets. Despite the tragic circumstances surrounding his death, Scrapper Blackwell’s legacy endures through his timeless contributions to the blues genre.

O.V. Wright, recognized for his powerful fusion of blues, soul, and gospel, brought unparalleled emotion-drenched intensity to his music. Born Overton Vertis Wright on October 9, 1939, in Lenow, Tennessee, near Memphis, he began his musical journey singing church music and later professionally with the Sunset Travelers.

O.V. Wright, recognized for his powerful fusion of blues, soul, and gospel, brought unparalleled emotion-drenched intensity to his music. Born Overton Vertis Wright on October 9, 1939, in Lenow, Tennessee, near Memphis, he began his musical journey singing church music and later professionally with the Sunset Travelers.

Despite his deep roots in gospel, O.V. Wright transitioned to secular music, making a significant impact with his unique blend of blues. Wright’s early success came with the Goldwax label in Memphis, where his debut R&B record, “That’s How Strong My Love Is,” showcased his impressive vocal prowess. However, legal battles ensued over contractual obligations, eventually leading him to the Back Beat label owned by Don Robey of Peacock Records. Back Beat became the platform for many of Wright’s notable recordings, including hits like “You’re Gonna Make Me Cry” and “Eight Men, Four Women.” Willie Mitchell and the Hi Rhythm Section played a crucial role in shaping the sound of Wright’s music, leading to several successful collaborations in the ’70s, such as “Ace of Spade” and “A Nickel and a Nail.” Mitchell, known for his work with Al Green, praised Wright as his most consistent artist in the studio. Onstage, O.V. Wright delivered dynamic performances often likened to that of a preacher, seamlessly blending verses from the blues and the Bible.

While he found success on the chitlin circuit, health issues, a criminal record, and a narcotics conviction hindered his career. In his final years, Wright continued performing, leaving a lasting mark on stages across the country. He passed away on November 16, 1980, while performing at Joe’s Supper Club in Grand Bay, Alabama. His legacy lives on through a core global following that includes hip-hop artists who have sampled his music. In 2008, a group of fans honored him with a headstone, acknowledging his profound impact on the worlds of blues, soul, and gospel. Johnny Rawls and Otis Clay recorded a tribute CD, “Remembering O.V.,” ensuring that O.V. Wright’s contributions to music endure.

Lil’ Ed and The Blues Imperials stand as a testament to the enduring power of tight-knit, infectiously cheerful blues bands. Led by singer and slide guitar maestro Lil’ Ed Williams, the group, which includes his half-brother and bassist James “Pookie” Young, along with Mike Garrett on guitar and Kelly Littleton on drums, has been making music together for over thirty-five years.

Lil’ Ed and The Blues Imperials stand as a testament to the enduring power of tight-knit, infectiously cheerful blues bands. Led by singer and slide guitar maestro Lil’ Ed Williams, the group, which includes his half-brother and bassist James “Pookie” Young, along with Mike Garrett on guitar and Kelly Littleton on drums, has been making music together for over thirty-five years.

Their energetic brand of boogie blues finds its roots in the legacy of another Chicago slide master, Ed’s uncle and mentor J.B. Hutto, a Blues Hall of Fame inductee in 1985. The Blues Imperials, inspired by a TV commercial for Imperial margarine, burst onto the scene in 1986 when Alligator Records owner Bruce Iglauer invited them to record two songs for a compilation. In true Chicago blues lore fashion, the session turned into a lively party, resulting in 30 songs in three hours and securing Lil’ Ed and the Blues Imperials a contract for their debut album, “Roughhousin’.” This milestone allowed Lil’ Ed to bid farewell to his job at a local car wash.

Born on April 4, 1955, in Chicago, Ed Williams passionately embraced a style reminiscent of his uncle J.B., both vocally and instrumentally. Mirroring Hutto’s iconic look, Ed even dons a fez during performances. His acrobatic showmanship and humorous stage presence brought a good-time element to the blues, captivating audiences and earning him a dedicated following of fez-wearing “Ed Heads.” Despite a brief hiatus in the 1990s for solo projects, Lil’ Ed and The Blues Imperials regrouped, rejoining Alligator Records, and solidifying their status as label mainstays. With nine albums to their credit, the core quartet, occasionally featuring saxophonist Eddie McKinley, has consistently delivered upbeat live shows and recordings, embodying the trademark “Genuine Houserocking Music” associated with Alligator Records. The band’s energetic performances continue to perpetuate the spirit of their influences, including Hound Dog Taylor and the HouseRockers, ensuring that the legacy of Lil’ Ed and The Blues Imperials remains synonymous with high-octane blues that genuinely rocks the house.

Individuals – Business, Production, Media, & Academic

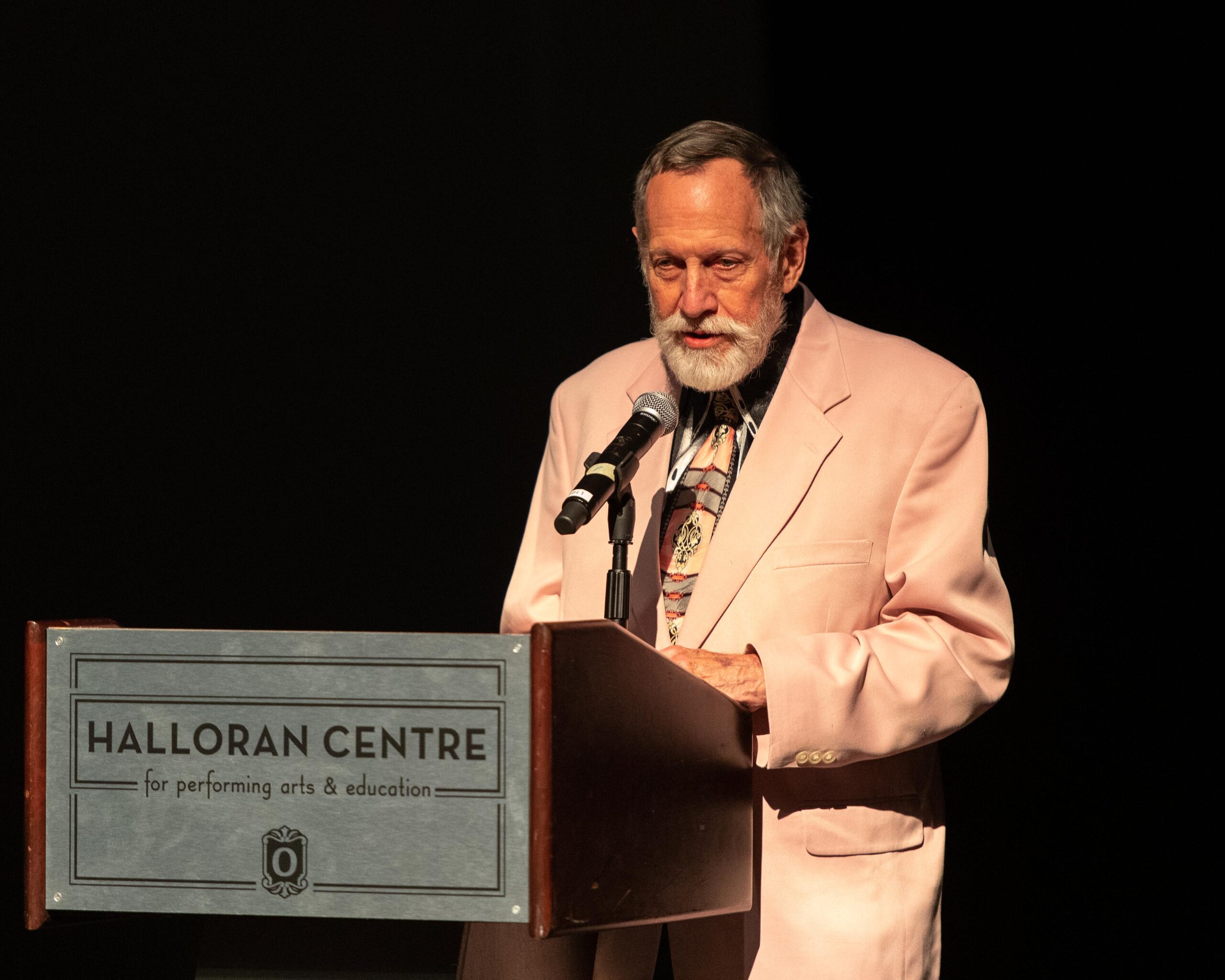

William R. “Bill” Ferris, a prominent figure in the world of blues, is celebrated for his multifaceted contributions as an author, folklorist, professor, lecturer, and administrator. Born on February 5, 1942, in Vicksburg, Mississippi, Ferris has played a pivotal role in documenting and preserving the rich cultural heritage of the American South, particularly in the realms of blues, gospel, and storytelling. Ferris initiated his work in the 1960s by recording, photographing, and filming blues musicians, gospel singers, and storytellers in Mississippi. His family’s farm in Vicksburg served as the backdrop for his early documentation efforts. Ferris focused not only on the musical aspects of the artists but delved into the broader context of their lives, folk traditions, and stories, providing a unique and comprehensive perspective on the cultural significance of the music within their communities. Having earned several college degrees, including a PhD in Folklore from the University of Pennsylvania, Ferris embarked on a career as an educator.

William R. “Bill” Ferris, a prominent figure in the world of blues, is celebrated for his multifaceted contributions as an author, folklorist, professor, lecturer, and administrator. Born on February 5, 1942, in Vicksburg, Mississippi, Ferris has played a pivotal role in documenting and preserving the rich cultural heritage of the American South, particularly in the realms of blues, gospel, and storytelling. Ferris initiated his work in the 1960s by recording, photographing, and filming blues musicians, gospel singers, and storytellers in Mississippi. His family’s farm in Vicksburg served as the backdrop for his early documentation efforts. Ferris focused not only on the musical aspects of the artists but delved into the broader context of their lives, folk traditions, and stories, providing a unique and comprehensive perspective on the cultural significance of the music within their communities. Having earned several college degrees, including a PhD in Folklore from the University of Pennsylvania, Ferris embarked on a career as an educator.

He taught at institutions such as Jackson State University and Yale University in the 1970s. Ferris co-founded the Center for Southern Folklore in Memphis and later directed the Center for the Study of Southern Culture at the University of Mississippi. His involvement in preserving blues history included hosting the “Highway 61” radio show and releasing recordings on the Southern Culture label. Ferris’s contributions extended to the acquisition of Living Blues magazine and significant materials, including B.B. King’s record collection, which formed the core of the Blues Archive at the University of Mississippi. He took on a role at the University of North Carolina in 2002 as a professor and Associate Director of the Center for the Study of the American South. His literary works, notably Blues From the Delta (1970) and Give My Poor Heart Ease: Voices of the Mississippi Blues (2009), showcase his commitment to exploring the social and cultural dimensions of the blues. Ferris’s comprehensive efforts received widespread acclaim, with Blues From the Delta earning recognition as a Classic of Blues Literature by the Blues Hall of Fame in 1998.

One of Ferris’s remarkable achievements is the Dust-to-Digital box set Voices of Mississippi: Artists and Musicians Documented by William Ferris, which won a GRAMMY in 2019. This extensive project includes multi-media presentations featuring live performances from renowned artists like Bobby Rush, Sharde Thomas, and Luther and Cody Dickinson, further solidifying Ferris’s impact on the preservation and celebration of Southern musical heritage.

Classic of Blues Literature

Blues Legacies and Black Feminism: Gertrude “Ma” Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday, by Angela Davis (Pantheon, 1998)

In Blues Legacies and Black Feminism, Angela Davis, controversial activist, author, and professor widely known for her revolutionary politics, argues against some conventional views of women and their songs in the blues. The lyrics sung by Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith and Billie Holiday, presented in the more than 200 transcriptions in this book, embodied strength, social consciousness, and feminist power in Davis’ analysis. And, in contrast to the idealized social mores often expressed by the Black middle class and white society in popular music of the era, blues lyrics according to Davis manifested “provocative and pervasive sexual-including homosexual-imagery,” incorporating responses to violence, infidelity and misogyny. Sexual freedom was a critical right in the absence of true political and economic freedom in the aftermath of slavery. “The female figures evoked in women’s blues are independent women free of the domestic orthodoxy of the prevailing representations of womanhood,” Davis wrote. Her interpretations, ideology and academic writing style met with mixed reviews, but Davis’ defense of the blues heroines has challenged readers to look deeper into these women’s art and the struggles that led them to sing the blues. Davis is also the author of Women, Race and Class and Women, Culture and Politics.

Biographies and descriptions written by Jim O’Neal (www.bluesoterica.com) with research assistance from Bob Eagle and Robert Ford. The full entries for all Blues Hall of Fame inductees from 1980 to date are posted at https://blues.org/blues-hall-of-fame.

Classic of Blues Recording – Album

Here’s the Man!!! – Bobby Bland (Duke, 1962)

Here’s the Man!!!, Bobby Bland’s second full LP on the Houston-based Duke label, was loaded with the kind of first-rate blues and R&B that made Bland such an idol in his time. In common with other blues LPs of the era, the music wasn’t produced at an album session but was assembled primarily from singles recorded at different dates—in this case, in Chicago, Los Angeles and Nashville in 1961 and 1962 under the direction of master arranger Joe Scott. Highlights include a sterling rendition of “Stormy Monday Blues” that brought T-Bone Walker’s 1940s classic “Call It Stormy Monday” back to prominence, featuring a famous Wayne Bennett guitar solo; “Your Friends” and other exemplary slow blues; the urgent “Ain’t That Loving You”; and one of the hottest dance rave-ups ever, “Turn on Your Love Light.” Even the fanfare-fueled spoken introduction is a classic—“Here’s the man! I mean the man! The sensational . . . the incomparable . . . the dynamic . . . Bobby, Bobby Bland!”

The liner notes, co-written by the legendary, promotion man and journalist Dave Clark of later Malaco Records fame contain nuggets as well, like the little-publicized revelation that Bland and future celebrity Eddie Fisher served in the army together. Bland is billed both on the cover and the vinyl label as Dynamic Bobby Bland, and indeed he was.

Classics of Blues Recording – Singles

“Driving Wheel” – Junior Parker (Duke, 1961)

“Driving Wheel” was one of several older blues successfully reworked by Junior Parker with his smooth vocal expertise. Based on Roosevelt Sykes’ “Driving Wheel Blues” from 1936, the title equated the powered wheel of a locomotive that moves the train along with the man who provides his woman with everything she needs. The single, recorded in 1961, reached No. 5 in Billboard and No. 6 in Cash Box in the R&B category and also appeared in the lower regions of the pop charts in both publications that year. Among the subsequent cover versions was one by Al Green, who claimed Parker as a cousin. The first appearance of “Driving Wheel Blues” in discographies was by Pine Top Smith in 1929, but his rendition was never released.

“I Ain’t Got You”- Billy Boy Arnold (Vee-Jay, 1955)

Vee-Jay Records first recorded “I Ain’t Got You” by its star, Jimmy Reed, in July 1955, but Billy Boy Arnold recalled in his autobiography that writer-producer Calvin Carter wanted a “swingin’, upbeat” version—which Billy Boy Arnold and guitarist Jody Williams provided at a session October. Arnold’s single hit the streets in early 1956 and later inspired cover versions by the Yardbirds (with Eric Clapton) and others. Reed’s version stayed in the vaults until it was out on an LP in 1960. Carter’s memorable lyrics pictured a player who has a charge account at Goldblatt’s (a Chicago discount store), a winning number in the policy racket, women all around, and more—but “ain’t got you.”

“Key to the Highway” – Jazz Gillum (Bluebird, 1940)

“Key to the Highway” becomes the first song elected to the Blues Hall of Fame twice—first by Big Bill Broonzy in 1941 and now by a Broonzy colleague, Jazz Gillum. Broonzy was better known than both Gillum and the first singer to record the song in 1940, Chares Segar, but it was Gillum’s version, cut on May 1, 1940, with Broonzy on guitar, that many preferred with its more down-home, plaintive vocals and harmonica. The record was popular enough to be issued as a single on RCA Victor and Groove after its first release on Bluebird. Composer credits on the oft-covered classic are confusing: Segar was credited on his version, Segar and Broonzy were cited as co-writers on Broonzy’s, and Gillum got sole credit on his. Furthermore, the performing rights organization BMI lists B.B. King, Muddy Waters, John Lee Hooker, Brownie McGhee and Mick Jagger/Keith Richard as composers of their various cover versions.

“Okie Dokie Stomp”- Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown (Peacock, 1954)

Gatemouth Brown’s instrumental prowess was on full display on his 1954 classic “Okie Dokie Stomp.” Brown’s nonstop guitar masterpiece was recorded with hot backing by the Pluma Davis Orchestra in Houston in May 1954. Bandleader-trombonist Davis was credited with composing the piece. In attempts to curry favor with radio DJs, who were all-important in the ‘50s, record labels sometimes named releases after them, and “Okie Dokie” was a nod (with a spelling change) to New Orleans’ popular WBOK jock James “Okey Dokey” Smith.

“Why Don’t You Do Right?” – Lil Green (Bluebird, 1941)

“Why Don’t You Do Right?” was a pop hit for Peggy Lee with Benny Goodman and his Orchestra in 1942 and the song originated as “Weed Smoker’s Dream” on a 1936 record by the Harlem Hamfats (sung and co-written by Kansas Joe McCoy), but it was Lil Green’s moody April 23, 1941, version, revised by McCoy, that became the classic in the blues world. “Why don’t you do right, like some other men do,” she sultrily declared, “Get out of here and get me some money too.” Green, one of the most popular blues singers of the ‘40s, was backed on the Chicago session by Big Bill Broonzy on guitar, Simeon Henry on piano and Ransom Knowling on bass.

2023 Blues Hall of Fame Inductees

PERFORMERS

Esther Phillips, began her career as an astounding 13-year-old prodigy, singing very adult, saucy blues with the legendary Johnny Otis revue in Los Angeles. Hers was a life filled with both triumphs and tragedy, cut short by the effects of heroin addiction, but less than a year before her death famed critic Leonard Feather hailed her as “the indisputable queen of the blues” in a nightclub review. A superlative singer who could deliver blues, R&B, soul, jazz, pop, and even country songs with candor and conviction, Phillips was a devotee of an earlier blues queen, Dinah Washington and often sang in the same vein while developing her own personal approach. He could play many instruments and might take a turn at the piano onstage but on recordings she focused only on her vocals.

Esther Mae Jones was her legal name when she started singing, but her birth surname was Washington, as registered in Galveston, Texas, on December 23, 1935. In a restart in later years she chose Phillips, inspired by a Phillips 66 sign. But to the blues/R&B world she was simply Little Esther in her teenage era. Raised in Houston and Los Angeles, she sang in church but wrapped herself in the blues early on. Accounts vary as to how she and Johnny Otis met, but the key event was a talent contest at the Barrelhouse Club which Otis co-owned in Watts. Under his auspices she made her first record for the Modern label on August 31, 1949, and soon she was recording hits with Otis on the Savoy imprint, including three consecutive No 1 R&B hits in 1950: “Double Crossing Blues,” “Mistrustin’ Blues,” and “Cupid’s Boogie.” Subsequent sessions for Federal and other labels produced some top-notch singles but sales fell off. Little Esther traveled with Otis and band (and initially with her mother, sister and a tutor) and showed impressive poise at the start, according to Otis’ producer Ralph Bass. While life on the road was exciting, it also deprived her of a normal adolescence. She turned to drugs and would go through periods of recuperation, relapse, and rehabilitation for the rest of her life. In 1962 Ray Charles’ monumental success with Modern Sounds in Country & Western Music motivated Lenox Records to employ Esther’s vocal expertise in a country setting. The result was one of her biggest hits, “Release Me.” The Lenox connection resulted in a contract with Atlantic Records and a few more hits including a Beatles cover, “And I Love Him,” which led to a BBC-TV appearance co-starring with the Fab Four. Jazz-inflected blues fueled the fine Atlantic albums Burnin’ and Confessin’ the Blues. Extensive studio crews of top musicians in jazz, funk and soul backed Phillips during the ‘70s on albums for the Kudu label (seven of which made the soul charts in Billboard), followed by releases on Mercury. Her Kudu update of Dinah Washington’s What a Diff’rence a Day Makes was her last big hit, but more striking was her emotionally charged rendition of Gil Scott-Heron’s heroin addiction masterpiece “Home is Where the Hatred Is.” The Kudu LP From a Whisper to a Scream earned her a Grammy nomination for Best R&B Vocal Performance of 1972. She lost, but the winner, Aretha Franklin, felt that Phillips deserved it and delivered the Grammy to her. Franklin said, “I gave her my Grammy because Esther was fighting personal demons, and I felt she could use encouragement. As a blues singer, she had her own thing; I wanted Esther to know that I – and the industry – supported her.” Phillips’ final album for Muse Records was posthumously titled A Way to Say Goodbye. The toll of drug and alcohol use alcohol abuse on her body led to her demise at a hospital in Torrance, California, on August 7, 1984. She was married to agent-producer Clyde B. Atkins, former husband of another of Phillips’ idols, Sarah Vaughan, in 1979 but had filed for divorce. Johnny Otis, with whom she had periodically reunited for guest appearances, preached her funeral and helped raise funds for a headstone. The Los Angeles music community has held several celebrations in her memory. Inducted in 2023 The Blues Foundation’s Hall of Fame. -Jim O’Neal, BluEstorica.com

Josh White, transitioned from a career as a traditional Piedmont blues artist to emerge as a unique and integral voice in the burgeoning folk music world of the 1940s, and in so doing played a seminal role in introducing new audiences to the blues. White was outspoken in his songs of protest against racism and injustice, a revolutionary tactic among blues singers of his era who had to couch such sentiments in code or hidden meanings in their lyrics. His induction into the Blues Hall of Fame and concurrent honors as Folk Alliance International’s 2023 Lifetime Achievement memorial award recipient are finally shining the spotlight on an icon whose many contributions have too often been forgotten or overlooked in the years since his death in 1969. Born in Greenville, South Carolina, on February 11, 1914, White sang in church as a youngster and got an extended taste of the road by traveling as a guide (or “lead boy”) for blind street singers. John Henry “Big Man” Arnold, his main local employer, also hired him out to other blind men and White claimed to have led Blind Lemon Jefferson and dozens of others. He also told of suffering beatings and witnessing a lynching. In 1928 he was in Chicago playing guitar behind Blind Joe Taggart on a session for Paramount Records. After returning to Greenville, he headed to New York City and launched his own recording career in 1932, chosen as one of a select crew of blues artists who were able to record prolifically in the Depression years. His blues and gospel records for the A.R.C. label group, many of them solo, some with accompanists including Leroy Carr and Walter Roland, were variously credited to Joshua White, Pinewood Tom, and Joshua White (The Singing Christian). An invitation to appear in a 1940 Broadway play, John Henry, in 1940, served as an entrée into a whole new realm of musical, theatrical, social, intellectual and political circles. White adroitly adapted his act to project folk authenticity with a sophisticated touch. His records, previously marketed to African Americans, changed accordingly to appeal to a predominantly white following. While he always drew on his blues and gospel repertoire, he also incorporated Tin Pan Alley hits, pop tunes, work songs, and folk ballads from various sources. His most popular number, “One Meat Ball,” recorded for Asch Records in 1944, was a bigger hit when covered by the Andrews Sisters, and many listeners heard “House of the Rising Sun” for the first time through White. More momentously, he began addressing segregation, workers’ rights, lynching and other controversial issues in songs such as “Defense Factory Blues,” “Uncle Sam Says,” and “Jim Crow Train” (written in collaboration with Harlem poet Waring Cuney), and “Strange Fruit,” the haunting vision of lynching first made famous by Billie Holiday, on Keynote and other labels. The resultant commotion drew the attention of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who met with White and became the first of three chief executives (prior to Kennedy and Johnson) to invite White to appear at presidential functions. Eleanor Roosevelt also became one of White’s closest confidantes. His other compatriots included Lead Belly, Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, Alan Lomax, Burl Ives, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee. Celebrated for his suave stage presence, supple guitar work, engaging showmanship, proper diction and sexual magnetism (plus offstage escapades), he appeared at cabarets, folk gatherings, and political events, on radio and TV shows, and in plays and feature films. In 1950 he broke new ground taking the blues to England, France and Scandinavia, traveling on a goodwill tour with Eleanor Roosevelt. However, his protest songs and leftist associations led to a blacklisting during the McCarthy Anti-Communist era and he was called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1950. For a while work became harder to find in the U.S. but receptive audiences in England and other countries enabled him to keep performing and he toured and recorded prolifically. In 1949 his Ballads and Blues on Decca was, according to some researchers, the first blues record to be released in a newly introduced format – the 33 rpm LP. His Strange Fruit LP on Mercury followed in 1950. He also recorded for Columbia, ABC-Paramount, Blue Note, Elektra, Vanguard and labels in France, the U.K., Italy and Denmark. While in England, he came out with a book, The Josh White Guitar Method, followed in the U.S. by The Josh White Song Book. White remained a popular figure on the folk scene although his finances began to decline along with his health. Testimonies to his impact upon upcoming musicians, including the first wave off British blues rockers, are legion. He died during heart surgery in Manhasset, New York, on September 5, 1969. Salutes to White’s legacy have included a children’s book, The Glory Road: The Story of Josh White in 1982, a U.S. postage stamp with his image in 1998, an incisive biography by Elijah Wald, Josh White: Society Blues, in 2000, a “Cultural Heroes” bust sculpted from clay shown in several museums, a three-panel statue in his hometown of Greenville unveiled in 2021, and this year’s Folk Alliance and Blues Hall of Fame honors. His music has lived on through his children, especially Josh White Jr., who has been a folk musician virtually all of his life ever since appearing onstage with White at Café Society as a four-year-old. The belated recognition from the blues community has been attributed to the view that the polished act that served White so well in folk concerts and cabarets has not fit well with recent generations’ preferences in the blues. As Elijah Wald wrote in Living Blues back in 2001: “He did more than any artist until B.B. King to make the blues singer a recognized cultural icon, and his rediscovery as a seminal musical giant and a unique American voice is long overdue.” Inducted in 2023 The Blues Foundation’s Hall of Fame. -Jim O’Neil, BluEstorica.com

John Primer, earned his pedigree in blues playing with Blues Hall of Famers Muddy Waters, Willie Dixon and Magic Slim. Still dedicated to the fundamentals he picked up as a sideman and apprentice, Primer now delivers consistently top-notch, no-nonsense blues on his steady slate of shows and recordings. He has been a perennial nominee and frequent victor in the Traditional Blues categories of the Blues Music Awards, Living Blues Awards and other honors programs. Primer’s life story reads like those of many blues greats who preceded him – born in Mississippi, raised in poverty, working the fields as a youngster, moving to Chicago for a factory job, cutting is teeth playing blues for tips at the Maxwell Steet outdoor market, making his way up through the club circuit, learning from the veterans, and maturing into an internationally heralded artist. The saga began in Camden, Mississippi, where Primer was born into a sharecropping family on March 5, 1945. Music provided a relief from daily hardships as he sang in church, played a homemade one-string guitar, and listened to his grandmother’s blues records. In 1963 he came to Chicago and was soon playing with local groups, eventually landing gigs in the house band at the fabled Theresa’s Lounge where he was mentored by guitar wizard Sammy Lawhorn while backing an all-star parade of guests, and at the Checkerboard, Buddy Guy’s home base. In 1979 Willie Dixon invited Primer to join his Chicago Blues All Stars, which gave Prime his first opportunities to tour outside the U.S. When Muddy Waters needed a new band in 1980, Primer found himself playing with one of his lifelong idols until Muddy’s death I 1983. Then began a 13-year stint with Magic Slim & the Teardrops, marked by constant touring and frequent recording, live and in the studio, with Primer regularly featured on a few vocals. Primer left to focus on his own career and began compiling an impressive resume of tours and albums, beginning with the first of several CDs for an Austrian label, Wolf Records, and continuing with Earwig, Code Blue (Atlantic), Telarc and others, including the label he and his wife Lisa own, Blues House Productions. He has been even more prolific in the studio as a first-call sideman in Chicago, recording with James Cotton, Jimmy Rogers, John Brim, Eddie Shaw and many more, along with live recordings with Muddy, Big Mama Thornton and others. His latest CD project, released in February 2023, is a tribute to Magic Slim. His aptly named Real Deal band features Steve Bell, son of Carey Bell, on harmonica. John Primer remains committed to honoring past heroes while creating his own music and passing the blues torch on to younger generations. Inducted in 2023 The Blues Foundation’s Hall of Fame -Jim O’Neal, BluEstorica.com

Snooky Pryor, was one of the pioneers of the classic Chicago blues of the post-World War II era, a byproduct of the migratory wave of musicians from Mississippi and the Deep South who changed the sound of the city with their electrified update of Delta blues. After playing a bugle (and harmonica) through a P.A. system while serving in the war, Pryor bought a P.A. system with speakers in Chicago and became one of the first harp players to amplify his sound with electricity. Pryor made some historic recordings for several Chicago labels, including Boogie (Snooky and Moody’s Boogie), a predecessor to Little Walter’s massive hit Juke, and Judgment Day (later revived by British rockers the Pretty Things and Eric Clapton), but none sold well enough to make the charts. He had some success in the city’s nightclubs but finally dropped off the scene in the 1960s, disillusioned with the music business. Rumors and questions about his whereabouts puzzled blues fans and researchers for years. Some thought he had turned to preaching or to Islam. Neither was true, although he was the son a preacher who forbade “devil music” (the blues) in the home, and he could quote the Bible at length. But on a phone call one night in 1971, guitarist Homesick James told Living Blues magazine that he had an old friend with him: “You know Snooky Pryor?” Pryor and his family had moved to Ullin in southern Illinois, where he was working as a carpenter. An article in the magazine led to a musical revival for Pryor, who resumed his recording career and went on to play concerts, clubs and festivals to an enthusiastic new generation of international blues aficionados. He picked up where he had left off, singing and playing the same spirited kind of blues he had perfected in the 1950s, eschewing the influences of subsequent soul, funk and rock music trends that changed the approach of many others in Chicago. Born in rural Quitman County, Mississippi, near Lambert and Denton, on September 15, 1919 (not 1921 as he usually said), James Edward Pryor took up harmonica and the blues in spite of his father’s rules. A childhood friend was future Chicago legend Jimmy Rogers, who was then nicknamed Snooky. Bluesman Floyd Jones later dubbed Pryor as Snooky (pronounced to rhyme with “nuke” rather than “nook”) in Chicago. Pryor left home as a teenager and traveled through Mississippi, Arkansas, Missouri, and Illinois, finally settling in Chicago, where his musical partners included Floyd and Moody Jones, Homesick James, Johnny Young and Eddie Taylor. His first Chicago recordings for Planet, J.O.B., Parrot and Vee-Jay have all been reissued on CD and LP. After his 1960s hiatus he cut his first album on the Today label, followed by a slew of others in the U.S., Europe and Canada for Big Bear, Blind Pig, Antone’s, Wolf, Electro-Fi and other companies. Though he made occasional Chicago appearances and worked for a while with Willie Dixon’s Chicago Blues All Stars, he continued to reside in Ullin, where he trained his sons Earl and Richard (“Rip Lee”) to play. Rip Lee has continued to perform in the venerated style of his father, who died in a Cape Girardeau, Missouri, hospital, on October 18, 2006. Inducted in 2023 The Blues Foundation’s Hall of Fame -Jim O’Neal, BluEstorica.com

Carey Bell, Harrington took his place in the lineage of Chicago blues harp masters in the 1970s, exuberantly following in the footsteps of his mentors Big Walter Horton and Little Walter Jacobs. In addition to recording noteworthy albums of his own, he became Chicago’s go-to harmonica player for blues sessions, valued for his creative solo flights and the ease with which he adapted to any song put before him. Bell made is first studio recordings backing guitar virtuoso Earl Hooker in November 1968 and over the next three decades he played on more than 100 different sessions, either as the featured artist or backing Willie Dixon, Muddy Waters, Louisiana Red, Jimmy Rogers, Eddy Clearwater and many others. He duetted on some with Big Walter Horton and other harp masters and joined James Cotton, Junior Wells and Billy Branch for a historic Harp Attack! album on Alligator. His good-natured, often playful live performances could generate even more excitement when he had the chance to extend his melodic explorations on both on the 10-hole diatonic harmonica and the larger chromatic instrument. Born Cary (sic) Harrington in Macon, Mississippi, on November 14, 1936, he began playing harmonica as a child and by the time he was in his teens he had come under the wing of veteran pianist Lovie Lee in the nearby city of Meridian. Lee took a young band including his “adopted stepson” Bell to Chicago in the mid-1950s and over the years they wove their talents into the Windy City blues fabric while holding down other jobs to make a living. Guitarist Honeyboy Edwards also guided the young Bell, playing with him and introducing him to both Little Walter and Big Walter. Edwards also showed Bell some runs on the bass, an instrument Bell learned to play with expertise. Bell also worked with Johnny Young, Eddie Taylor, ad others and was recorded in a street performance with Robert Nighthawk at the Maxwell Street market in 1964. Earl Hooker hired Bell for a tour to play bass, and then harmonica when he learned how well Bell could play. After his recording session with Hooker for Arhoolie, Bell played on a Sleepy John Estes session for Delmark and waxed his own Delmark debut LP, Carey Bell’s Blues Harp, in 1969. His career immediately shifted into high gear with regular club gigs, festivals and tours, including several junkets to Europe. Muddy Waters brought Bell into his band, as did Howlin’ Wolf briefly, followed by a stint with Willie Dixon’s Chicago Blues All Stars, in between his own gigs and sessions. Albums of his work, some co-billed with his son Lurrie Bell, a phenom himself, appeared on ABC BluesWay, Alligator, Blind Pig, Wolf, Rooster Blues, L+R, Blues South West, JSP and other labels in the U.S. and several other countries. His Alligator CD Good Luck Man won a W.C. Handy Award in 1998, the same year he was elected Traditional Male Blues Artist of the Year, following several previous nominations. Among his other accomplishments he sired a brood of blues-playing sons including Lurrie, Steve (now playing harp in classic Carey Bell style in John Primer’s band), Tyson and James. He had moved to North Carolina and lived with Willie Dixon’s daughter Patricia before entering a Chicago hospital where he died of pneumonia and renal failure on May 6, 2007. A diabetic, Bell had suffered a stroke in 2006 but the joy of making music never left him and he recorded tracks for his final CD onstage in a wheelchair. Inducted in 2023 The Blues Foundation’s Hall of Fame -Jim O’Neal, BluEstorica.com

Fenton Robinson, practiced an erudite brand of blues hailed by musicians, critics and discerning audiences around the world, but rarely enjoyed the kind of wide public acclaim enjoyed by many high energy, hard-rocking blues performers. As Alligator Records’ Bruce Iglauer wrote, “In a world of barroom entertainers Fenton Robinson was a serious musician who is best appreciated with greater concentration than his audience usually gave him.” Robinson relocated to different cities several times trying to find his niche and had his moments of success and satisfaction, as a performer, songwriter and teacher. His 1967 masterwork “Somebody Loan Me a Dime” failed the hit the national charts but scored in Chicago, enough so that Robinson was recruited to compete with B.B. and Albert King, Bobby Bland and other heavyweights in a “Battle for King of the Blues” show at the Regal Theater in 1968. A 1969 rendition by Boz Scaggs with Duane Allman on guitar was the first of many cover versions. Robinson did the first waxing of the often-recorded standard “As the Years Go Passing By,” which he said was written by Peppermint Harris. “You Don’t Know What Love Is,” an Alligator album track, also inspired covers. Born in Leflore County in the Mississippi Delta on September 23, 1935 (or a little before, according to various documents), Robinson began performing as a teenager in Memphis, where he teamed with guitarist Charles McGowan. He and McGowan moved to Little Rock and briefly to St. Louis. Robinson made his first records for the Meteor label in Memphis and Duke Records in Houston, playing with a harder electric attack than on his later Chicago records when he had developed a nimble, fleet-fingered technique influenced by T-Bone Walker’s style and by formal music studies. In addition to “As the Years Go (Passing) By,” his 1950s records (all credited to Fention Robinson) included “Tennessee Woman,” “The Freeze (made famous by Albert Collins) and, on a session backing Little Rock cohort Larry Davis, “Texas Flood” (later popularized by Stevie Ray Vaughan). Robinson moved to Chicago in 1961 and established himself on the club scene, backing Junior Wells, Sonny Boy Williamson No. 2, Otis Rush and others and working his own gigs on the strength of singles he recorded for USA, Giant and Palos that showcased both his progressive guitar work and sensitive, soulful vocals. HIs debut LP on Nashville’s Sound Stage 7 label captured his talent as a vocalist but allotted little room for his guitar. His upward trajectory was blunted after a 1969 auto accident which eventually landed him in prison, but a letter-writing campaign from blues fans helped him earn an early release. He was based in Chicago in the 1970s, aside from a stay in Santa Cruz, California, where he landed after partnering on tour with Charlie Musselwhite. He recorded two critically acclaimed albums for Alligator, including the Blues Hall of Fame LP I Hear Some Blues Downstairs. But his career in Chicago stagnated and he decided to move back to Little Rock, where he had been well received on return visits. Springfield, Illinois, where he had earlier taught blues in the schools, was his next residence, followed by Rockford, Illinois. Although he toured across the country and overseas, made further high-quality recordings, and was widely admired, high-echelon blues stardom eluded him. A philosophical thinker, serious reader and progressive musician, Robinson embraced the Islamic faith in the 1970s and once went under the name Fenton Lee Shabazz. A Japanese reissue LP honored him with the title The Mellow Blues Genius, and a British album designated him Mellow Fellow. He passed away from cancer in Rockford on November 25, 1997.

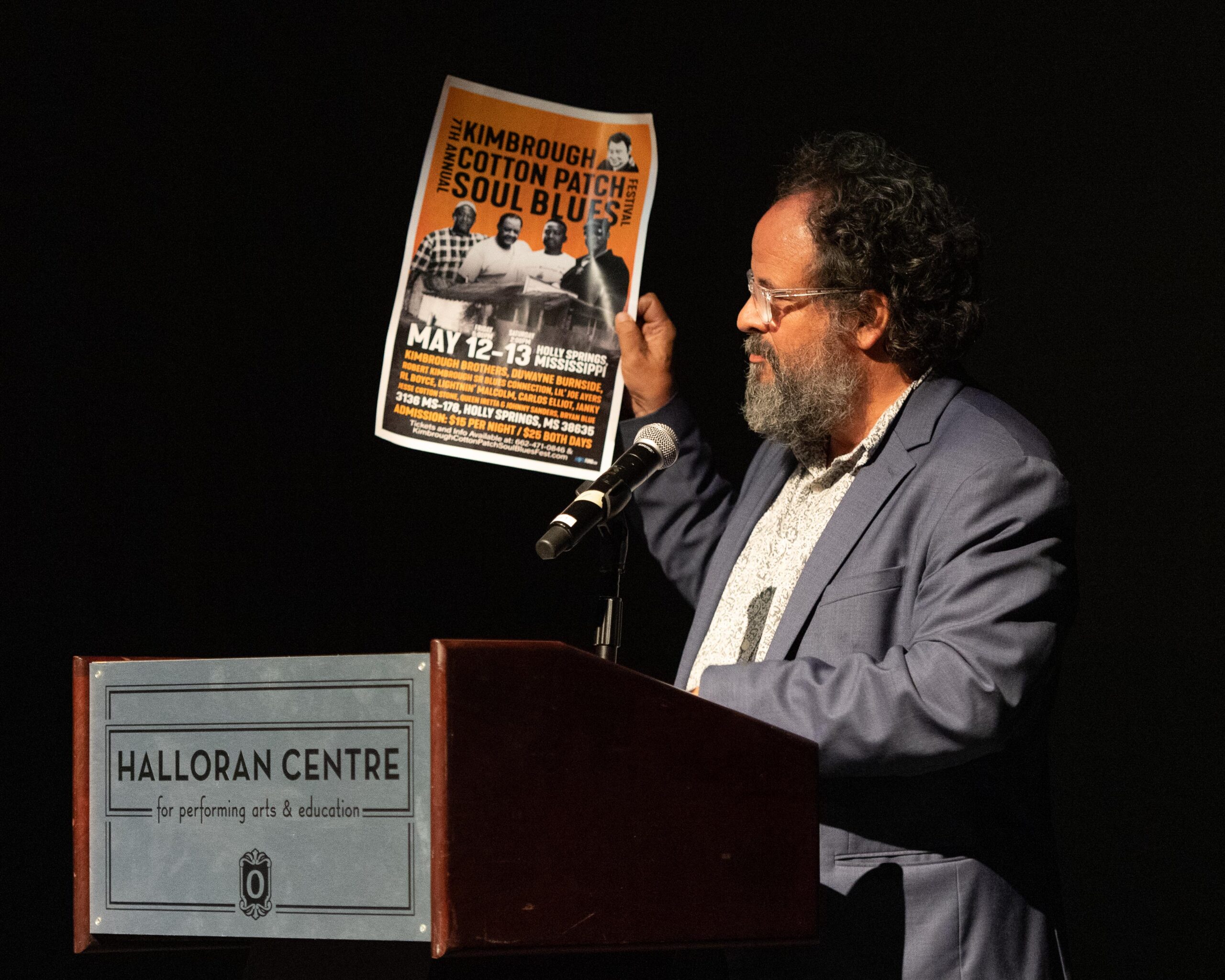

Junior Kimbrough, after years of holding forth in the juke joints and house parties of the Mississippi hills, Junior Kimbrough became a nationally renowned blues icon known both for his unique idiosyncratic style and for his role as potentate at his own juke, Junior’s Place, where visitors from far and wide mingled with the party crowd of Marshall County. Kimbrough called his music cotton patch blues or cotton patch soul blues, a custom maintained by his family of musicians, and like other Hill Country blues variants, its foundation lay in a raw, insistent groove. The Kimbrough style—not as hotly energized as the rocking rhythms of his friend R.L. Burnside or an early influence, Mississippi Fred McDowell — employed a droning, hypnotic roll that won him followings among both blues fans and devotees of trance and alternative rock. David Kimbrough Jr. was born in Hudsonville, Mississippi, on July 28, 1930, He grew up in a musical family which included his father (his most formative influence) and several siblings and sang in a gospel group before assembling his own blues band. Rockabilly legend Charlie Feathers, a longtime friend from Hudsonville, helped Kimbrough secure his first record release, a single on the Philwood label in Memphis in 1966. Another Memphis session for Goldwax was shelved until the sides appeared on a First Recordings collection in 2009. Likewise, a 1969 recording with Feathers and 1980s album for the University of Memphis’ High Water imprint remained unissued until Kimbrough’s later fame prompted their release. High Water did issue a 1982 Kimbrough single which revealed the sound he had developed with his group, the Soul Blues Boys. It was not until his performance of his signature tune “All Night Long” in the documentary Deep Blues and several albums for the Fat Possum label in the 1990s that his fame truly spread. He played festivals in America and Europe but did not tour frequently. Instead, his audience (including some famous rock stars) came to him, especially at his juke joint in Chulahoma where he also recorded some of his CDs. His bands typically included some of his sons and younger members of the Burnside family (who once lived next door). His music was perpetuated by his sons David Malone (1965-2019), Kinney Malone and Robert Kimbrough and grandson Cameron Kimbrough, and his songs have been covered by the Black Keys, Iggy Pop & the Stooges, Daft Punk, the North Mississippi Allstars and others. Kimbrough died of a heart attack in Holly Springs Memorial Hospital on January 17,1998. His legacy is celebrated annually in the area at the Kimbrough Cotton Patch Soul Blues Festival. His headstone bears the memorable quote from Charlie Feathers, “Junior Kimbrough is the beginning and end of all music.” Inducted in 2023 The Blues Foundation’s Hall of Fame -Jim O’Neal, BluEstorica.com

INDIVIDUALS

BUSINESS, PRODUCTION, MEDIA, or ACADEMIC

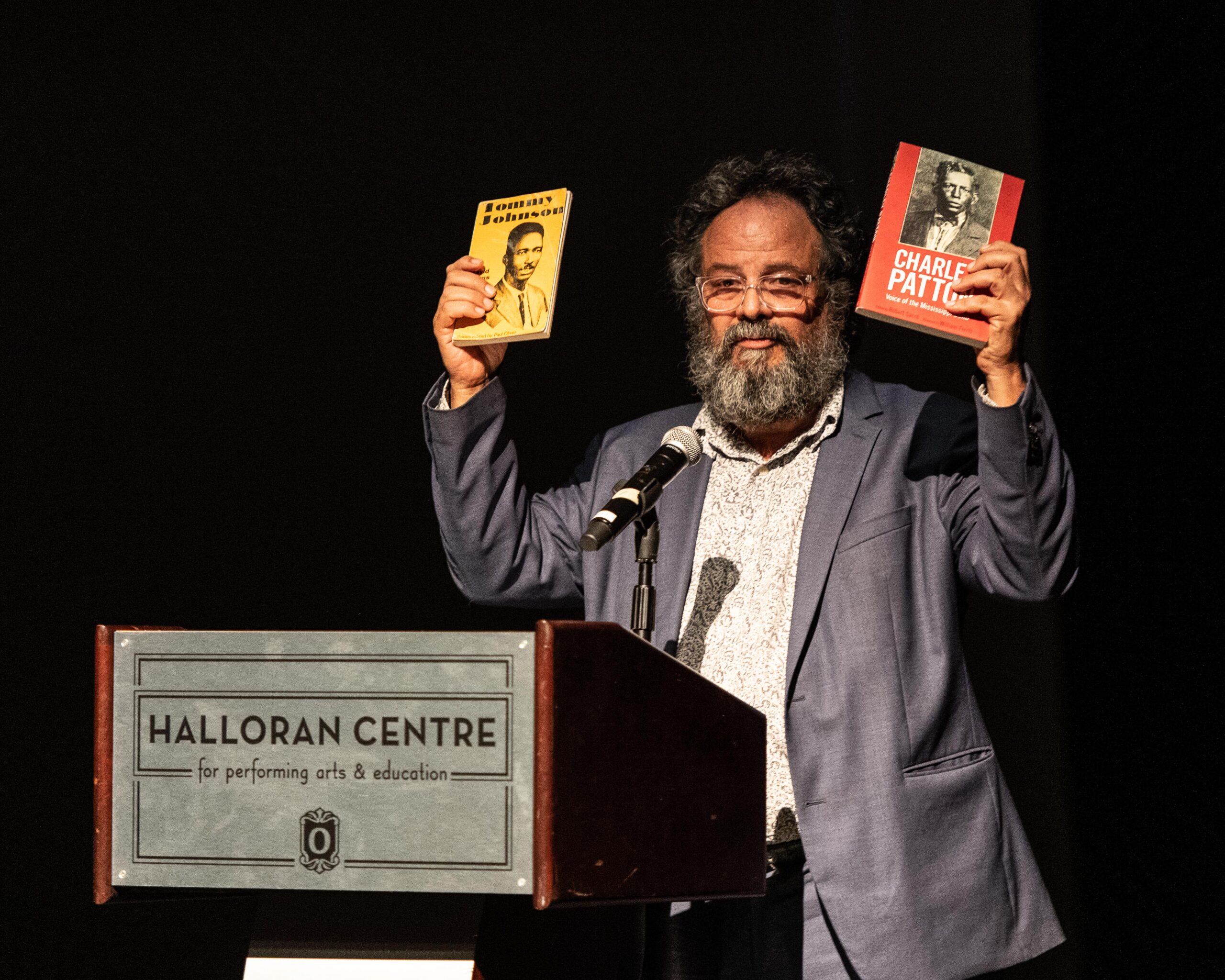

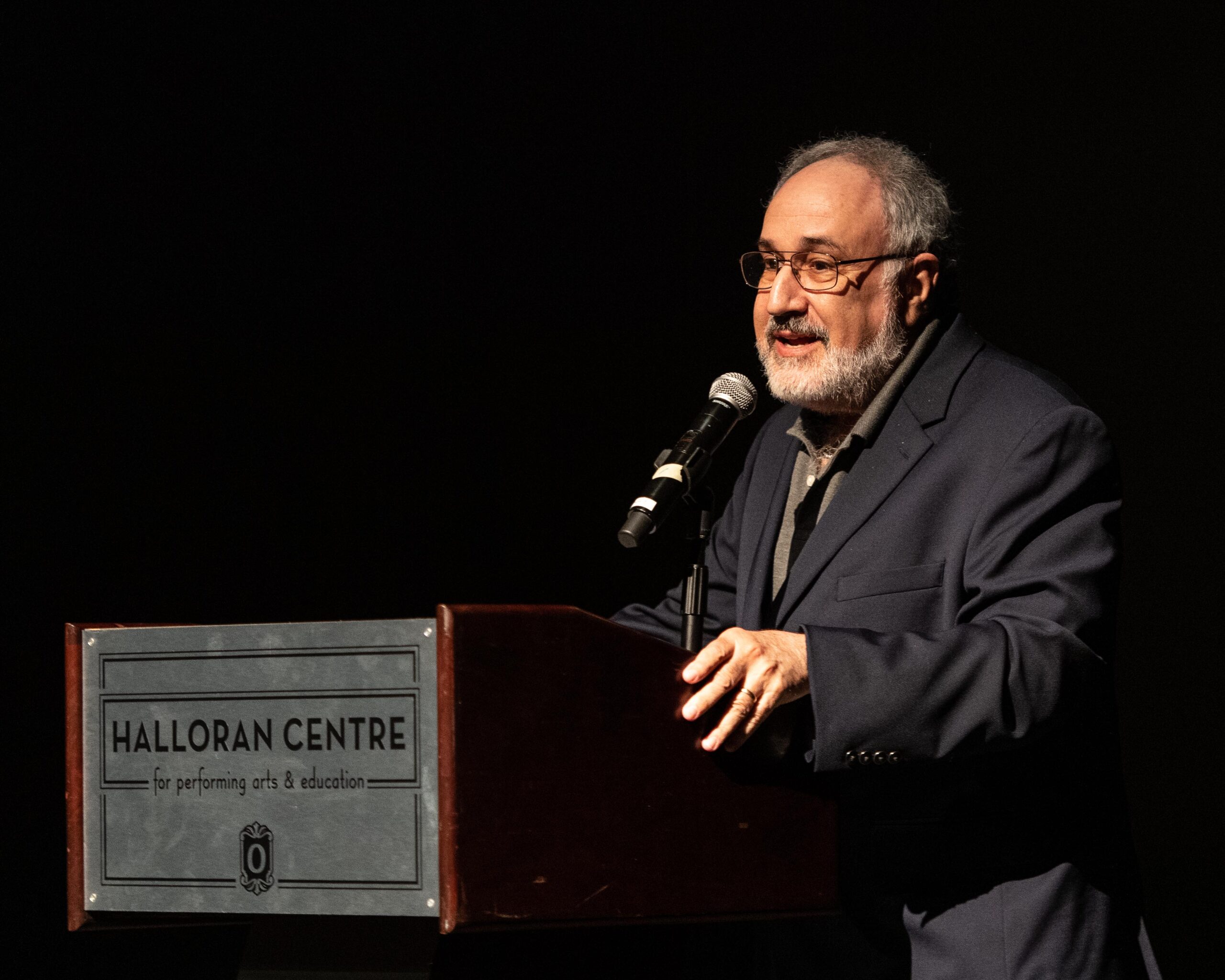

David Evans’ induction in a Blues Hall of Fame category covering “Business, Academic, Media & Production” achievements could not be more fitting, for he has covered multiple bases as an educator, field researcher, and producer with hundreds of media credits in print and in audio and video formats. While not a businessman in an occupational sense, Evans has had to handle plenty of business with blues artists, record companies, and at events around the world, including his own extensive travels as a performing musician. Evans is the author of four books on the blues, including Big Road Blues: Tradition and Creativity in the Folk Blues, which is in Blues Hall of Fame. He taught from 1978 to 2016 at the University of Memphis, where he was in charge of the university’s High Water record label as well as its ethnomusicology curriculum and other classes. He produced records by R.L. Burnside, Jessie Mae Hemphill and many other artists for High Water and for a variety of other labels and did groundbreaking research on blues legends Tommy Johnson and Charley Patton, as well as on the blues and fife and drum traditions of the Mississippi Hill Country and the community of Bentonia, home of Skip James and Jack Owens. Born in Boston on January 22, 1944, Evans graduated from Harvard before earning degrees in folklore and mythology at UCLA and teaching at California State-Fullerton. His scholarly research and his fieldwork in Mississippi, Louisiana and other states formed the basis for a plethora of publications, recordings, liner notes and lectures. His writing has been informed by a multidisciplinary approach utilizing musicology, biography, history, discography, folklore studies and his experience as a musician. He has been the recipient of multiple research grants, academic honors and awards, including two Grammys for liner notes. Beyond the blues, he has also done research in Africa and Venezuela, and in America with gospel singers, the Hopi Indian nation and others. At the University of Memphis his students included blues authors Kip Lornell and Steve Franz and many other writers, educators and producers. Evans’ film and video work includes a Mississippi fife and drum documentary and an instructional video on the guitar style of Tommy Johnson, while his radio resume is highlighted by two long-running shows he hosted in Memphis on WEVL. Evans has served as a series editor at the University Press of Mississippi since 1996. The series numbers over 100 books, including The Original Blues, this year’s Blues Hall of Fame honoree in the Classics of Blues Literature category, and his latest book, Going Up the Country: Adventures in Blues Fieldwork in the 1960s. David Evans, Inducted in 2023 The Blues Foundation’s Hall of Fame -Jim O’Neal, BluEstorica.com

CLASSIC OF BLUES LITERATURE

CLASSIC OF BLUES RECORDING – ALBUM

Little Walter Jacobs was the best blues harmonica player ever, in the opinion of many fans and musicians, and certainly the most influential, so Hip-O’s 5-CD, 126-track compilation of his work was a true blues bonanza. The set includes all the material issued on Chess Records’ Checker subsidiary including such classics as “Juke,” “My Babe,” and “Blues With a Feeling,” along with unissued tracks. The variety in sounds, styles and accompaniments enhances the collection, which features stellar sidemen like Muddy Waters, Robert Jr. Lockwood, Buddy Guy, Fred Below, Willie Dixon and many more. Scott Dirks, Tony Glover ad Ward Gaines, co-authors of Walter’s biography, contributed the liner notes. According to a recent communique from Dirks, “The Hip-O box includes every completed take of every title in Little Walter’s Chess discography except for one minor leftover,” an instrumental version of “One of These Mornings” that is shorter than the take chosen for the box by compiler Andy McKaie.

CLASSICS OF BLUES RECORDING: SINGLE

Black Nights– Lowell Fulson (Kent, 1965) Lowell Fulson (or Fulsom, as Kent Records spelled it) excelled as a songwriter, singer and guitarist, and “Black Nights” is one of his finest works and biggest hits, charting for 12 weeks in 1965-66 in Billboard magazine. Fulson’s poignant lament of faded love and lonely black nights was recorded during one of his most productive periods in 1965 on the Bihari brothers’ Kent label with stalwart arranger Maxwell Davis on piano.

I’m Tore Down – Freddy King, (Federal, 1961) “I’m Tore Down,” a tale of despondency set to a shuffle rhythm, was written by producer-pianist Sonny Thompson and sung with appropriate verve by Freddy (aka Freddie) King, who also contributed some of his signature piercing guitar licks. Recorded January 18, 1961, with Thompson and a studio band in Cincinnati, it became the fifth of King’s six entries on Billboard’s R&B charts that year and is the second of them (after the instrumental “Hide Away”) to enter the Blues Hall of Fame.

My Black Mama — Son House (Paramount, 1930) “My Black Mama” may not be a title familiar to the many admirers of Son House’s work during his revived 1960s career, but while the title was never used for any the songs he recorded then, the original 1930 version is loaded with couplets recognizable in many other songs by House and by blues singers before and after him, from Ida Cox to Robert Johnson. While the record is nominally about a black woman who’ll “make a mule kick his stable down,” House floated in a variety of verses including several from “Death Letter Blues.” House’s bold vocal delivery and concise guitar accompaniment make this a prime example of his deep Delta blues in his prime, recorded at Paramount’s studio in Grafton, Wisconsin, in 1930.

The Red Rooster (Little Red Rooster) — Howlin’ Wolf (Chess, 1961) “The Red Rooster,” better known as “Little Red Rooster,” is widely acknowledged as one of Howlin’ Wolf’s classics, but oddly enough it was not a major hit when Chess Records released it as a 45 rpm single in 1961. It didn’t chart for Chess, but it did much better for Sam Cooke in 1963 in the U.S. and for the Rolling Stones, whose version hit No. 1 in the U.K. in 1964. Wolf’s original featured not only his incomparable vocals but also his rarely featured slide guitar. Willie Dixon drew on an old theme recorded by Memphis Minnie as “If You See My Rooster” to compose his own version of the song.

We invite you to listen to The Blues Foundation Podcast!

Season 1: Blues Hall of Fame centers on a different Blues Hall of Famer, and explores a specific moment in their life.

Produced by Beale Street Caravan. Written by Preston Lauterbach. Voiced by Guy Davis.

LISTEN NOW

Blues Hall of Famers Speak the Blues

Bobby Rush

Elvin Bishop

Become a Member

Becoming a member of The Blues Foundation gives you an opportunity to be personally connected to a blues community where you will experience a vast amount of resources, information, news, views, insight, and activities not available anywhere else. You will become part of this fantastic Blues family which shares your love of the Blues, past, present and future.

Photos by Roger Stephenson

Donate

Since 1980, The Blues Foundation has been inducting individuals, recordings, and literature into the Blues Hall of Fame, but until recently there has not been a physical home to celebrate their music and stories. Building the Blues Hall of Fame Museum has fulfilled one of our key goals – The creation of a space to honor inductees year-round; to listen to and learn about their music; and to enjoy historic mementos of this all-American art form. The new Blues Hall of Fame is the place for serious blues fans, casual visitors, and wide-eyed students. It facilitates audience development and membership growth. It exposes, enlightens, educates, and entertains. The Blues Hall of Fame opened May 8, 2015.