FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

March 17, 2022

LUCILLE BOGAN, LITTLE WILLIE JOHN, JOHNNIE TAYLOR, OTIS BLACKWELL, AND MARY KATHERINE ALDIN WILL BE CELEBRATED AS NEW BLUES HALL OF FAMERS ON MAY 4, 2022

Landmark recordings by:

Bobby “Blue” Bland, Roy Brown, Bo Diddley, B.B. King,

Baby Face Leroy Trio, and Sonny Boy Williamson II

To receive Hall of Fame recognition at The Blues Foundation’s ceremony in Memphis

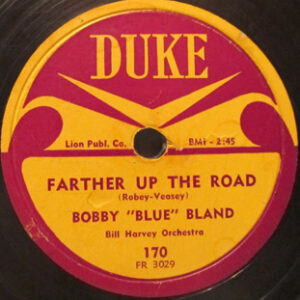

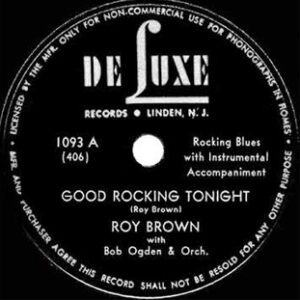

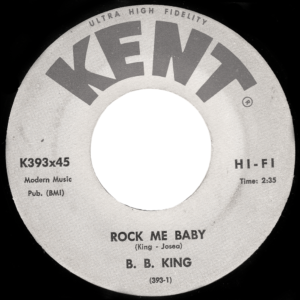

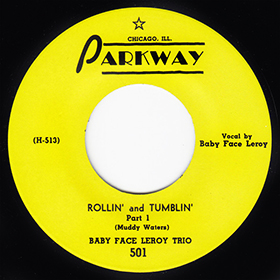

MEMPHIS, Tenn. — The 12 honorees of The Blues Foundation’s Blues Hall of Fame’s 42nd class encompass over 70 years of music, spanning from Lucille Bogan in the 1920s & 1930s, Little Willie John in the 1950s & 1960s, and Johnnie Taylor from the 1950s through the 1990s. This year’s inductees in the Blues Hall of Fame’s five categories — Performers, Individuals, Classics of Blues Literature, Classics of Blues Recording (Single), and Classics of Blues Recording (Album) — demonstrate how the blues intersects with a wide variety of American music styles: soul, blues, R&B, and rock’ n’ roll.The new Blues Hall of Fame performers aren’t just exceptional musicians, but they also are educators, innovators, entrepreneurs, and activists determined to leave their mark on the world.Lucille Bogan recorded some of the most memorable songs of the pre-World War II era, recording from 1923-1935 for Okeh, Paramount, Brunswick, Banner, Melotone, and other labels. Her songs were covered by B.B. King, John Lee “Sonny Boy” Williamson, Jimmy Rogers, Memphis Minnie, and others, but she became more well known for the controversial themes her music embodied. Little Willie John was a soul, blues, and rock ‘n’ roll star whose meteoric rise and tragic fall ended when at age 30 he died in prison. Labeled as a “singer’s singer” by none other than B.B. King, this blues and ballad vocalist extraordinaire had his first national hit while still a teenager. Ten of his records crossed over to the pop charts, which landed him three appearances on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand. Johnnie Taylor spent his early years as a solo performer singing gospel, although his first recording was as a member of the doo-wop group, The Five Echoes. While signed to Stax from 1966-1974, he recorded his breakthrough single “Who’s Making Love.” His next biggest hit came with the 1976 platinum-selling “Disco Lady.” Later, Taylor took his gospel-influenced blues, soul, and funk to Malaco, where he found a new home for his music until the end. While he never met Elvis Presley, Otis Blackwell is best known for writing Presley’s massive hits, “Don’t Be Cruel,” “All Shook Up,” and “Return To Sender.” He’s also credited as writing “Breathless” and “Great Balls of Fire” for Jerry Lee Lewis as well as the Little Willie John/Peggy Lee hit, “Fever.” He recorded for RCA Victor, the Jay-Dee label, and others but avoided the limelight finding his niche in songwriting. Mary Katherine Aldin has spent the past 60 years behind the scenes in the blues and folk music worlds, as a voice on the radio and as compiler or annotator of blues and folk reissue albums for Rhino, Vanguard, MCA/Chess, Columbia, and other labels. She was nominated for a GRAMMY® for her liner notes for The Chess Box by Muddy Waters. Aldin also served in various editorial positions at Living Blues, Blues & Rhythm, and others and secured publishing rights for artists at Folklore Productions. She was inducted into the Folk DJ Hall of Fame in 2018 and is still broadcasting for KPFK’s “Roots Music & Beyond.” Bo Diddley’s Bo Diddley is 2022’s Classic of Blues Recording: Album, which compiled 12 of his groundbreaking singles on Chess Records’ Checker subsidiary. There are five Classic of Blues Recording: Singles receiving Hall of Fame induction: Sonny Boy Williamson II’s 1951 single “Eyesight to the Blind” the first release by the master harmonica player and singer, Bobby “Blue” Bland’s 1957 hit “Farther Up the Road,” Roy Brown’s 1947 release “Good Rocking Tonight” hit No. 1 on the R&B charts when covered by Wynonie Harris, B.B. King’s “Rock Me Baby” released in 1964 was one of his biggest hits on the Billboard pop charts, and the exuberant “Rollin’ and Tumblin’” released in 1950 by the Baby Face Leroy Trio.Entering the Blues Hall of Fame as a Classic of Blues Literature is Red River Blues: The Blues Tradition in the Southeast, written by British author Bruce Bastin and hailed as an acclaimed work of blues scholarship.

Due to the global shutdown in 2020 that forced The Blues Foundation to cancel in-person fundraisers, the celebration of the 2020 Blues Hall of Fame Inductees will officially take place along with the 2022 ceremony. Honorees include Billy Branch, Eddie Boyd, Syl Johnson, Bettye LaVette, George “Harmonica” Smith, Victoria Spivey, Ralph Peer, and more. Read the original 2020 press release here.

Bo Diddley’s Bo Diddley is 2022’s Classic of Blues Recording: Album, which compiled 12 of his groundbreaking singles on Chess Records’ Checker subsidiary. There are five Classic of Blues Recording: Singles receiving Hall of Fame induction: Sonny Boy Williamson II’s 1951 single “Eyesight to the Blind”was the first release by the master harmonica player and singer, Bobby “Blue” Bland’s 1957 hit “Farther Up the Road,” Roy Brown’s 1947 release “Good Rocking Tonight” which hit No. 1 on the R&B charts when covered by Wynonie Harris, B.B. King’s “Rock Me Baby” recorded in 1947 was one of his biggest hits on the Billboard pop charts, and the exuberant “Rollin’ and Tumblin’” released in 1950 by the Baby Face Leroy Trio.

Entering the Blues Hall of Fame as a Classic of Blues Literature is Red Rover Blues, written by British author Bruce Bastin and is the definitive study of traditional blues from the Southeastern United States.

Due to the global shutdown in 2020 that forced The Blues Foundation to cancel in-person fundraisers, the celebration of the 2020 Blues Hall of Fame Inductees will officially take place along with the 2022 ceremony. Honorees include Billy Branch, Eddie Boyd, Syl Johnson, Bettye LaVette, George “Harmonica” Smith, Victoria Spivey, Ralph Peer, and more. Read the original 2020 press release here.

The Blues Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony, held this year in conjunction with the Blues Music Awards and International Blues Challenge week, will occur on Wednesday, May 4, 2022, at the Halloran Centre (225 S. Main St., Memphis). A cocktail reception honoring the BHOF Inductees and Blues Music Awards nominees will begin at 5:30 p.m., with the formal inductions commencing at 6:30 p.m. in the Halloran Theater. Tickets, including the ceremony and reception, are $75 each and are available with Blues Music Awards tickets here.

Coinciding with the Induction Ceremony, The Blues Foundation’s Blues Hall of Fame Museum will showcase several special items representing the 2020 and 2022 class of inductees. These artifacts will be on display for public viewing beginning the first week of May and will remain on view for visitor enjoyment for the next 12 months.

The Blues Hall of Fame Museum, built through the ardent support and generosity of blues fans, embodies all four elements of The Blues Foundation’s mission: preserving blues heritage, celebrating blues recording and performance, expanding awareness of the blues genre, and ensuring the future of the music.

The museum’s current exhibit in the upstairs gallery features the work of music photographer Jérôme Brunet. This exhibition features blues legends and Blues Hall of Famers such as B.B. King, Robert Cray, Etta James, Mavis Staples, Honeyboy Edwards, and Johnny Winter to name just a few. Museum visitors can also explore the permanent exhibits and individualized galleries that showcase an unmatched selection of album covers, photographs, historical awards, unique art, musical instruments, costumes, and other one-of-a-kind memorabilia. In addition, interactive displays allow guests to hear the music, watch the videos, and read the stories about each of the Blues Hall of Fame’s over 400 inductees.

The museum will re-open in late April with amended hours that will be listed here. Admission is $10 for adults and $8 for students with I.D.; free for children 12 and younger and for Blues Foundation members. Membership is available for as a little as $25 per person; to join, visit www.blues.org. The Blues Foundation’s Blues Hall of Fame Museum is located at 421 South Main Street in Memphis, TN.

The Blues Foundation’s partners and sponsors include ArtsMemphis, Tennessee Arts Commission, Memphis Tourism, BMI, and Legendary Rhythm & Blues Cruise.

The Blues Foundation’s 2022 Blues Hall of Fame Inductees

Blues Hall of Fame Inductee biographies and descriptions were researched and written by Jim O’Neal (bluesoterica.com) with thanks to Bob Eagle, Bob McGrath, John Broven, Roger Armstrong, Larry Cohn, Malaco Records, and Roger Naber.

Performers

Lucille Bogan recorded some of the most memorable blues songs of the pre-World War II era, including some that were landmarks in blues and some that continue to sensationalize her reputation decades after her death. She was the first African-American singer to record blues at a session outside of New York or Chicago when she sang at sessions for OKeh Records set up in a warehouse in Atlanta in 1923, and several of her records were later covered or adapted by various artists who preceded her into the Blues Hall of Fame. But by far the predominant association now made with Bogan is the lewdness of two unexpurgated songs she recorded in 1935 that were not intended for public release.

Lucille Bogan recorded some of the most memorable blues songs of the pre-World War II era, including some that were landmarks in blues and some that continue to sensationalize her reputation decades after her death. She was the first African-American singer to record blues at a session outside of New York or Chicago when she sang at sessions for OKeh Records set up in a warehouse in Atlanta in 1923, and several of her records were later covered or adapted by various artists who preceded her into the Blues Hall of Fame. But by far the predominant association now made with Bogan is the lewdness of two unexpurgated songs she recorded in 1935 that were not intended for public release.

Sexual references were common in blues recording but the proprieties of the day called for them to be disguised in double entendre form. Bogan made a number of those, but presumably, for the entertainment of the recording staff and friends, she used explicit language in “Till the Cows Come Home” and an alternate take of “Shave ’Em Dry” that makes most hardcore rap lyrics seem tame. Though these were “private” recordings, bootleg pressings made their way into circulation and eventually were transferred to legitimate albums in more permissive modern times.

Bogan, however, had already long been a favorite among blues collectors and historians for the depth of her talent and recorded repertoire, and was a significant artist in the blues market of the 1920s and ‘30s. She lacked the name recognition of some of her contemporaries because most of her records were released under the pseudonym, Bessie Jackson.

Some of her songs embodied controversial themes including prostitution, lesbianism, and—since most were recorded during prohibition—drinking. Some veteran researchers doubt that she lived the rough street life she sometimes sang about, but her lyrics did reflect a familiarity with the underside of polite society. Bogan’s 1923-1935 recordings for OKeh, Paramount, Brunswick, Banner, Melotone, and other labels featured various notable accompanists including Will Ezell, Tampa Red, and Walter Roland. Among her influential records that survived via later artists were the first version of “Black Angel Blues” (later recorded by Tampa Red and Robert Nighthawk, and by B.B. King as “Sweet Little Angel”), “Sloppy Drunk Blues” (Leroy Carr, John Lee “Sonny Boy” Williamson, Jimmy Rogers, and others), and “Tricks Ain’t Walking No More” (Memphis Minnie).

Railroad references also cropped up in her songs, not surprisingly since her father, brother, and husband all worked for the railroad in Birmingham, Alabama, or Amory, Mississippi. Both towns have been purported as her birthplace (as Lucille or Lucile Anderson on April 1, 1897). Misinformation and speculation on her life is rampant on the internet, where Amory is most often cited. She and other relatives did live in Amory at times, but most census entries indicate Alabama, and Bogan herself gave Birmingham as the site on her Social Security application. She returned to the Birmingham area in between stays in Amory, Chicago, and elsewhere. Her brother Thomas “Big Music” Anderson was a musician, as was her son Nazareth Bogan Jr., whose group Bogan’s Birmingham Busters she reportedly managed. A few months before her death on August 10, 1948, she had moved to Los Angeles and kept a hand in the music business, as a song posthumously crediting her as writer appeared on a record on the L.A.-based Specialty label by bluesman Smokey Hogg.

The meteoric rise and tragic fall of William Edward “Little Willie” John, who died in prison at the age of 30, is one of the most dramatic chapters in rhythm & blues history. A “singer’s singer” in the words of some (including one of his early inspirations, B.B. King), John was a pioneer of soul music, a rock ‘n’ roll star, and a blues and ballad vocalist extraordinaire who burst on the national scene as a teenager with the hit “All Around the World” in 1955. Born in Cullendale, Arkansas, on November 15, 1937, John grew up in Detroit, singing with his family’s gospel group (including sister Mable John, who also became a blues and soul singer) before he started sneaking out to nightclubs and theaters. He cut his first record, a Christmas single, for the local Prize label, in 1953. “All Around the World” (later recorded by Little Milton as “Grits Ain’t Groceries”) was the first song he waxed for King Records and was followed by 16 more R&B chart hits for the label over the next six years, including “Need Your Love So Bad,” “Talk to Me, Talk to Me,” “Heartbreak,” “Take My Love,” and, most famously, the original version of “Fever.” Ten of his records also crossed over to the pop charts, and John rode the wave of success headlining shows across the country and appearing three times on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand.

Small (five feet four and 126 pounds, according to his biography by Susan Whitall and John’s son Kevin) and boyish in appearance, John was a sharply attired and exciting showstopper, recalled by fellow singers as mischievous, fun-loving, and generous. But offstage troubles, drinking, and drugs took a toll on his career and lifestyle. An altercation at an after-hours party in Seattle in 1964 led to a manslaughter conviction, and he died on May 26, 1968, at Washington State Penitentiary in Walla Walla. The official cause of death was cited as a heart attack, but other sources said John—who suffered from epilepsy—had contracted tuberculosis and some suspected he died from an assault in prison. James Brown, both a friend and rival, later recorded an album, Thinking About Little Willie John and a Few Nice Things, and was one of many who have sung his praises and recorded his songs over the years. John was elected to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1996. The Susan Whitall-Kevin John biography is aptly titled Fever: Little Willie John—A Fast Life, Mysterious Death and the Birth of Soul.

Johnnie Taylor liked to emphasize that he could sing more than blues, as indeed he amply proved when performing gospel and soul, but among African-American audiences, he reigned as the top headliner of his era at blues events. Famed for his 1976 hit “Disco Lady,” Taylor set sales records for several labels and had more than three dozen hits on the national charts.

Gospel was Taylor’s forte in his early years, although he first recorded as a member of a doo-wop group, the Five Echoes, in 1954, in Chicago. Born on May 5, 1934, in Crawfordsville, Arkansas, Taylor was raised in West Memphis and Kansas City, where he sang gospel with the Melody Kings before he moved to Chicago. There he sang lead on most of the first songs recorded by the Highway Q-C’s gospel group in 1955-56 for the Vee-Jay label, and similarly took the lead role when he replaced Sam Cooke in the Soul Stirrers on their 1958-59 records for the Specialty imprint. Taylor became an ordained minister but followed Cooke into the secular world of rhythm & blues, cutting a series of records for Cooke’s SAR and Derby labels including “Rome (Wasn’t Built in a Day).” After Cooke’s death in 1964, Taylor, back in Kansas City with an uncertain future as an entertainer, enrolled in college. His career soon took an upturn when he signed with Stax Records in Memphis.

While he once sounded much like Sam Cooke, Taylor developed a more identifiable style incorporating gospel-influenced blues, soul, and funk during his tenure with Stax from 1966 to 1974. The company touted his 1968 hit “Who’s Makin’ Love” as “the fastest-selling single in the history of Stax Records,” and Taylor kicked his touring activity into high gear displaying a mix of polish and grit while continuing to hit the charts with his Stax recordings. In 1976 Taylor’s chart success peaked with “Disco Lady” on the Columbia label. The Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) instituted its platinum record category, symbolizing sales of a million units, that year, and the first platinum single award went to “Disco Lady.” By then residing in Dallas, Taylor hosted a local radio show and traveled to studios around the country to record for Columbia, but sales tailed off. He only truly his stride again when he began recording for Malaco Records of Jackson, Mississippi, the flagship of soul-blues labels where he likened the atmosphere to that at Stax. With two heart attacks a drug rehabilitation stint behind him, he recorded and toured as the top star of the “chitlin’ circuit,” purveying a mix of Southern soul and blues. His “Last Two Dollars,” “Still Called the Blues,” and “Wall to Wall” were among the favorites of blues followers. His Good Love album eclipsed Z.Z. Hill’s classic Down Home as Malaco’s best seller. Malaco owners Tommy Couch Sr. and Wolf Stephenson had decided to sign Taylor after hearing him sing at Hill’s funeral in Dallas. He also sang at the funeral of Little Willie John, among others. Taylor was honored with a Pioneer Award by the Rhythm and Blues Foundation in 1996.

Taylor, a Malaco artist until the end, succumbed to a heart attack on May 31, 2000, in Dallas. Among his children, he left several who carried on his music, including Floyd Taylor and Johnnie Taylor, Jr., who have both since passed on, T.J. Hooker Taylor in Kansas City, and Jon and Tasha Taylor in Los Angeles. The late Little Johnny Taylor, who recorded the Blues Hall of Fame single “Part Time Love,” was often confused with Johnnie Taylor, but the two were not related.

Individuals – Business, Production, Media, & Academic

Mary Katherine Aldin began six decades of service to the music world when she worked at the Ash Grove, the legendary Los Angeles folk club, not long after she moved from New York in 1962. The first in a series of radio shows soon followed and she is still broadcasting on KPFK’s “Roots Music & Beyond” following long tenures on “Preaching the Blues” and “Alive and Pickin’,” which earned her entry into the Folk DJ Hall of Fame in 2018. While working at a record store specializing in blues, she began annotating and compiling albums for Rhino Records and has since worked on blues, folk, bluegrass, and country reissues albums for Rhino, Vanguard, MCA/Chess, Columbia, Decca, Mercury, Smithsonian Folkways, Hightone, and other labels. Her notes to The Chess Box by Muddy Waters were nominated for a GRAMMY. Her writings include chapters in Nothing But the Blues and other books, and she once served as associate editor of Living Blues magazine and U.S. editor of the British periodical Blues & Rhythm: The Gospel Truth, in addition to publishing a Blues Magazine Selective Index and contributing photos to various publications and record companies.

For 25 years Aldin worked for Folklore Productions, where her duties included securing publishing rights for the traditional artists the agency represented. A co-founder of the Southern California Blues Society, she served as a festival MC and organized fundraising benefits. Along with the way, Aldin developed friendships not only with Willie Dixon, Muddy Waters, Big Joe Turner, Pee Wee Crayton, Long Gone Miles, George “Harmonica” Smith, Roy Brown, and others but also with many of their wives and children, who knew they could call on her for help if they needed to arrange or pay for funerals. Many archival materials from her historic body of work are now housed at the University of North Carolina and the University of Mississippi. Always intent on shining the spotlight on the music and performers and not on herself, one of her mottos has been “It’s the work, not the worker.”

Otis Blackwell was a struggling blues singer in New York City when he struck gold on a different path—writing songs for others to sing, and in particular, Elvis Presley. A fortunate meeting with a music publisher led Blackwell to submit a demo of his song “Don’t Be Cruel,” and Elvis—singing it much like Blackwell—made it into a No. 1 single for RCA Victor in 1956. Many other hits, written wholly or in part by Blackwell, were to follow, including “All Shook Up,” “Paralyzed” and “Return To Sender” for Elvis, “Breathless” and “Great Balls of Fire” for Jerry Lee Lewis, “Hey Little Girl” and “Just Keep It Up” for Dee Clark, and “Handy Man” for Jimmy Jones. Because of a conflicting contract with another publisher, Blackwell also wrote songs under his stepfather John Davenport’s name, most notably the Little Willie John/Peggy Lee hit “Fever.” His catalog at Broadcast Music, Inc. (BMI, the music rights organization that collects royalties for songwriters and publishers), numbers over 400 songs and he claimed to have written over 1000.

Otis Blackwell was a struggling blues singer in New York City when he struck gold on a different path—writing songs for others to sing, and in particular, Elvis Presley. A fortunate meeting with a music publisher led Blackwell to submit a demo of his song “Don’t Be Cruel,” and Elvis—singing it much like Blackwell—made it into a No. 1 single for RCA Victor in 1956. Many other hits, written wholly or in part by Blackwell, were to follow, including “All Shook Up,” “Paralyzed” and “Return To Sender” for Elvis, “Breathless” and “Great Balls of Fire” for Jerry Lee Lewis, “Hey Little Girl” and “Just Keep It Up” for Dee Clark, and “Handy Man” for Jimmy Jones. Because of a conflicting contract with another publisher, Blackwell also wrote songs under his stepfather John Davenport’s name, most notably the Little Willie John/Peggy Lee hit “Fever.” His catalog at Broadcast Music, Inc. (BMI, the music rights organization that collects royalties for songwriters and publishers), numbers over 400 songs and he claimed to have written over 1000.

Blackwell was born in Brooklyn on February 16, 1932 (although other dates are sometimes cited) and began singing and dancing in local bars in his youth. He recalled that many songs he wrote were based on piano boogies and shuffles he devised. Blackwell began recording for RCA Victor in 1952 and for various labels thereafter. “Daddy Rollin’ Stone” on the Jay-Dee label was the best known of his records but none of them reached the national charts.

Finding his niche as a songwriter and less enamored with performing, he tended to avoid the limelight–so much so that he never even met Presley or many other singers who recorded his songs. “We had just a great thing going and I just wanted to leave it alone,” Blackwell later said. “I just wanted to keep writing and let him do the singing.”

Blackwell enjoyed a moment of fame when he sang “Don’t Be Cruel” on Late Night with David Letterman in 1984, and, capitalizing on the interest his songwriting reputation had generated, he began performing again in later years with a repertoire of his compositions made famous by the stars. A Brooklyn resident most of his life, he lived his final years in Nashville, where he died on May 6, 2002.

Classic of Blues Literature

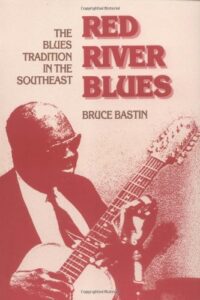

Red River Blues: The Blues Tradition in the Southeast was hailed as the definitive study of traditional blues from the Southeastern states when it was published in 1986, and it remains so today thanks to the thoroughness of author Bruce Bastin’s research. Bastin, an Englishman who earned a folklore degree at the University of North Carolina and co-founded the prolific Flyright record label in the U.K., covered all the seminal recording artists who emerged from the area as well as many who never recorded and were known only to local audiences. The biographies, data from record companies, census reports, sociological studies of various communities, and contributions of fellow researchers including Pete Lowry and Kip Lornell render this a densely packed volume, one of special interest to fans of Blind Boy Fuller, Reverend Gary Davis, Brownie McGhee, Sonny Terry, Blind Willie McTell, Josh White, Blind Blake and others who helped define the acoustic blues sound of the Carolinas, Virginia, Georgia and the surrounding areas.

Red River Blues: The Blues Tradition in the Southeast was hailed as the definitive study of traditional blues from the Southeastern states when it was published in 1986, and it remains so today thanks to the thoroughness of author Bruce Bastin’s research. Bastin, an Englishman who earned a folklore degree at the University of North Carolina and co-founded the prolific Flyright record label in the U.K., covered all the seminal recording artists who emerged from the area as well as many who never recorded and were known only to local audiences. The biographies, data from record companies, census reports, sociological studies of various communities, and contributions of fellow researchers including Pete Lowry and Kip Lornell render this a densely packed volume, one of special interest to fans of Blind Boy Fuller, Reverend Gary Davis, Brownie McGhee, Sonny Terry, Blind Willie McTell, Josh White, Blind Blake and others who helped define the acoustic blues sound of the Carolinas, Virginia, Georgia and the surrounding areas.

(University of Illinois Press, 1986)

Classic of Blues Recording – Album

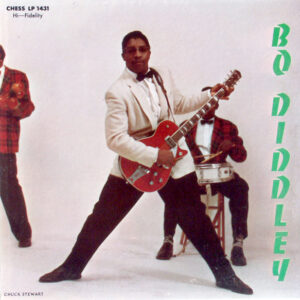

Bo Diddley was the stage name of Ellas McDaniel and the title of both his debut single and this, his first LP, which compiled 12 sides from the groundbreaking singles on Chess Records’ Checker subsidiary that made him a one-of-a-kind rock ‘n’ roll icon. Along with the “Bo Diddley beat” rockers are blues (including the original version of “I’m a Man”) and brash and boastful novelties from the fertile Diddley mind. Several of the 1955-58 sessions represented on the LP feature Bo with a cast of stellar Chicago bluesmen including Willie Dixon, Jody Williams, and Billy Boy Arnold.

Bo Diddley was the stage name of Ellas McDaniel and the title of both his debut single and this, his first LP, which compiled 12 sides from the groundbreaking singles on Chess Records’ Checker subsidiary that made him a one-of-a-kind rock ‘n’ roll icon. Along with the “Bo Diddley beat” rockers are blues (including the original version of “I’m a Man”) and brash and boastful novelties from the fertile Diddley mind. Several of the 1955-58 sessions represented on the LP feature Bo with a cast of stellar Chicago bluesmen including Willie Dixon, Jody Williams, and Billy Boy Arnold.

(Chess/Checker, 1958)

Classics of Blues Recording – Singles

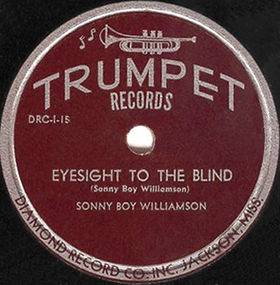

Rock fans may recognize “Eyesight to the Blind” as the only song from The Who’s rock opera Tommy that was not written by the band. This paean to a woman who could bring eyesight to the blind and heal the deaf and dumb came from Sonny Boy Williamson No. 2 (aka “Rice” Miller among many other names), who recorded it as an evocative blues piece for the Trumpet label in Jackson, Mississippi, in 1951. It was, in fact, the first record released by the master harmonica player and singer, and one of many to feature his poetic lyrical talents. Accompanying him on the session were guitarists Elmore James and Joe Willie Wilkins, pianist Willie Love, and drummer Joe Dyson.

(Trumpet, 1951)

Though famed for soft, romantic blues ballads, Bobby “Blue” Bland could wail hard-hitting blues, too, as he did in 1957 with the Bill Harvey Orchestra on “Farther Up the Road.” Guitarist Pat Hare’s menacing fills and sizzling solo push the intensity even higher. The song was copyrighted by Joe Medwick Veasey and Duke Records owner Don D. Robey as “Further On Up the Road,” which is the way Bland sings it. Joe Medwick, who dropped the Veasey from his stage name, later recorded as a singer for Duke and other labels in Texas.

(Duke, 1957)

A contender for the title of first rock ‘n’ roll record—or at least one that paved the way to rock, “Good Rocking Tonight” was a product of Cosimo Matassa’s legendary New Orleans studio where blues shouter Roy Brown and Bob Ogden’s Orchestra recorded in July 1947. DeLuxe Records released it as a single with some success but it was a cover version by Wynonie Harris on the King label that went to No. 1 on the R&B—or, as it was known then, “Race Music”—charts in 1948. Brown was still able to make it part of his trademark jump-blues sound and generated more sales with lively followups such as “Rockin’ at Midnight.” Elvis Presley’s 1954 Sun version introduced new listeners to the song, which has since been recorded by many blues, R&B, and rock singers.

(DeLuxe, 1947)

Many blues have been recorded on the “rock me” theme, but it was B.B. King’s 1964 single that climbed the charts and solidified the song as a standard in the blues canon. King’s other hits featured larger combos or orchestras, but only a trio played on this staunch, straight-ahead blues. It was one of his biggest hits on the Billboard pop charts and made both the R&B and pop charts in the rival trade magazine Cash Box. Kent Records’ documentation of sessions was scanty, with no recording date to be verified, but it was released in 1964 while King was under contract to ABC Records. Sources at Ace Records, the U.K. company that acquired Kent and other labels owned by the Bihari brothers of Los Angeles, have speculated that “Rock Me Baby” and others may have been the products of “midnight sessions” King recorded under the ABC radar.

(Kent, c. 1964)

Few records can match the raw exuberance of the Baby Face Leroy Trio’s two-part “Rollin’ and Tumblin’ ” on Parkway, a small and short–lived Chicago label. Muddy Waters and Little Walter join singer-drummer Leroy Foster on this rambunctious 1950 rendition of an old Hambone Willie Newbern tune. Part 2 has no verses at all—just a mélange of the trio’s moans, hums and yelps. When Leonard Chess heard the record, he had Muddy cut his own two-part version on Aristocrat, the label that preceded Chess Records. Muddy added more verses and delivered the goods but his record not did have the wild abandon of the original. When Little Walter’s fame later rocketed as a solo artist, the Herald label reissued Part 2 of the Parkway single as a Little Walter record, “Rollin’ Blues.”

(Parkway, 1950)